Air quality plays a central role in urban health and wellbeing. Clean air supports respiratory and cardiovascular function, with particular importance for children, older people, and those with pre-existing conditions. In cities, however, air pollution is largely shaped by traffic. Vehicle emissions concentrate pollutants in areas where people live, work, and move each day.

Brussels’ annual Day Without Cars is intended to address this problem directly. By encouraging residents to shift temporarily to more sustainable modes of transport, the initiative aims to reduce traffic emissions across the city. The rationale is straightforward: traffic-related pollution regularly reaches levels that are consequential for health and the urban environment.

Traffic emissions: what are we breathing?

Road traffic is a major source of urban air pollution, releasing particulate matter (PM) and nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), both of which are associated with adverse health effects. PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀ consist of fine dust particles that can penetrate deep into the lungs, while NO₂ is an irritant gas that can inflame airways and worsen conditions such as asthma.

The challenge is most visible in dense urban areas, where cars, buses, and trucks operate in close proximity to homes and public spaces. Urban green spaces are often assumed to mitigate this exposure. Parks are expected to act as buffers—absorbing pollutants, moderating heat, and offering cleaner air to visitors.

In Brussels, parks such as Parc du Cinquantenaire and Parc de Bruxelles (Royal Park) are deeply embedded in daily life, used by thousands of people, including children, older residents, and athletes. The open question is whether these spaces meaningfully reduce exposure to traffic-related pollution, particularly during peak hours.

Measuring the air in and around parks

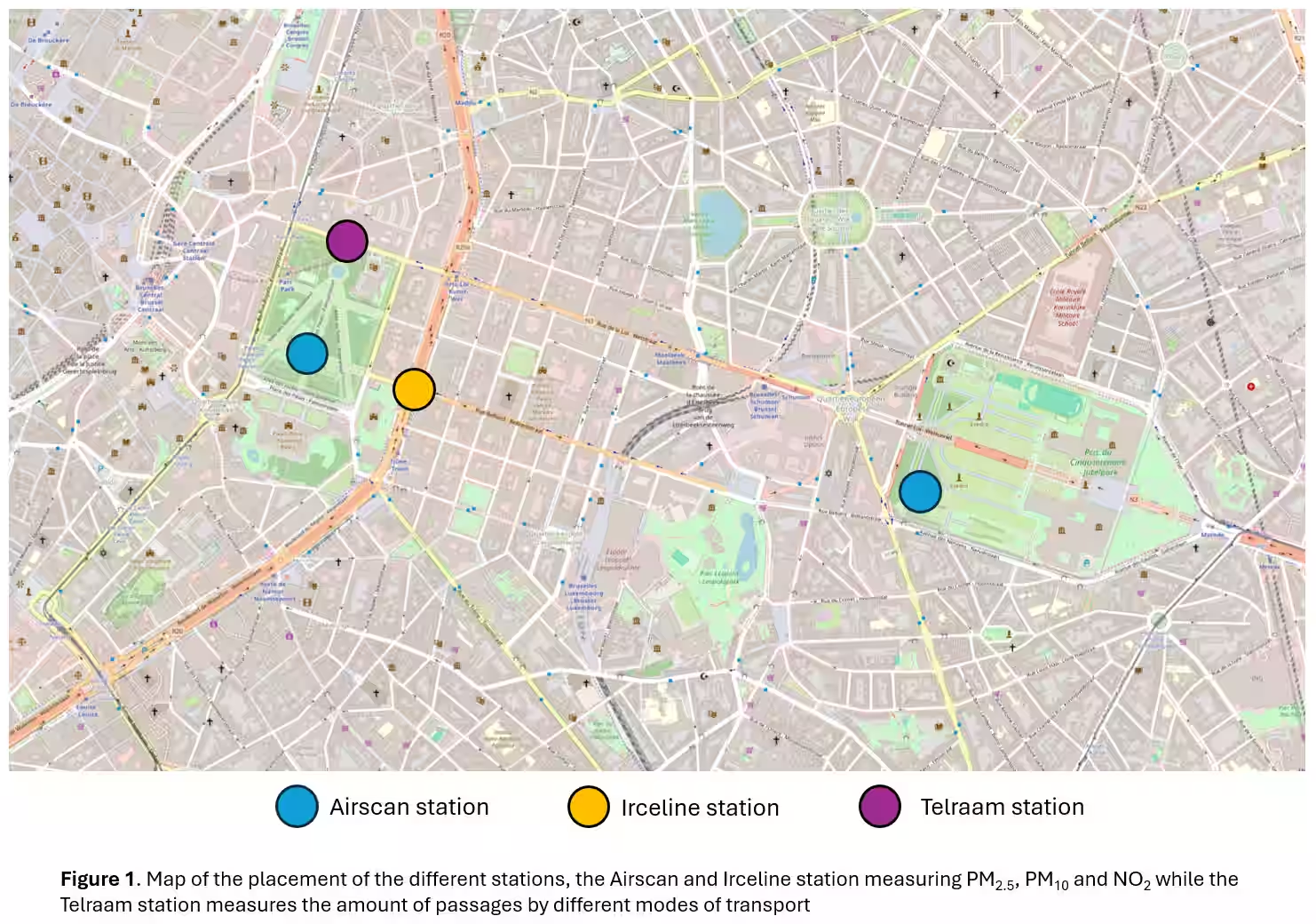

To examine this question, air-quality data were collected in Parc du Cinquantenaire and Parc de Bruxelles. Measurements focused on three pollutants: PM₂.₅, PM₁₀, and nitrogen dioxide (NO₂). Daily concentrations in the parks were compared with those measured during the Day Without Cars.

The underlying assumption was simple. If green spaces substantially mitigate urban pollution, pollutant concentrations should remain relatively stable when traffic is reduced. Marked differences would indicate a strong influence from surrounding roads.

For context, the World Health Organization recommends the following guideline values:

– PM₂.₅: 5 µg/m³

– PM₁₀: 15 µg/m³

– NO₂: 5 ppb

What the data shows in Brussels’ parks

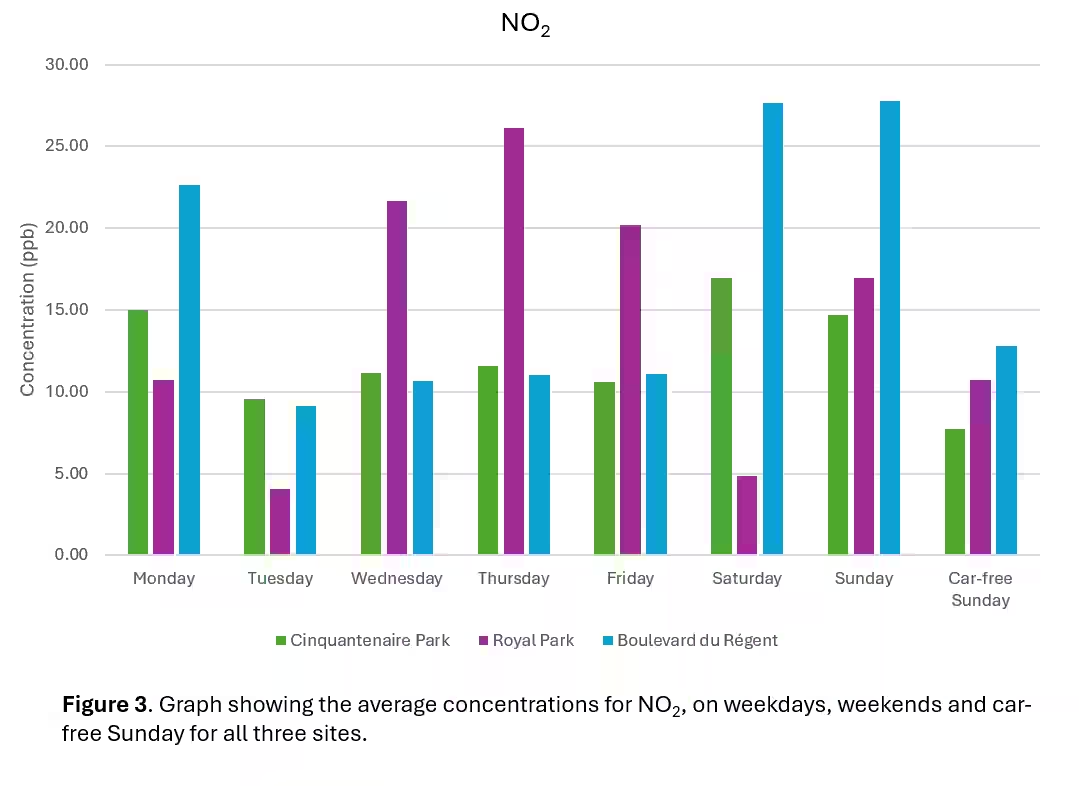

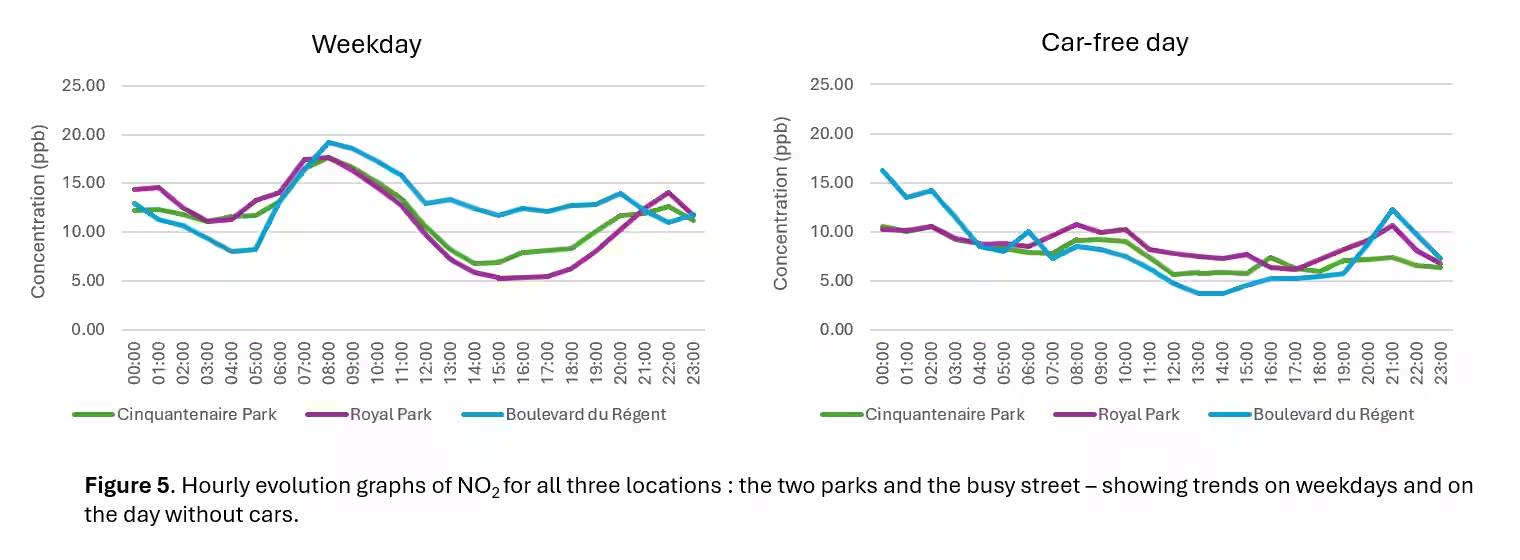

Nitrogen dioxide levels in the parks were generally higher during the working week, reflecting their proximity to busy roads. This pattern became more pronounced during colder periods, when weekend NO₂ concentrations increased on Boulevard du Régent—likely linked to higher car use in lower temperatures.

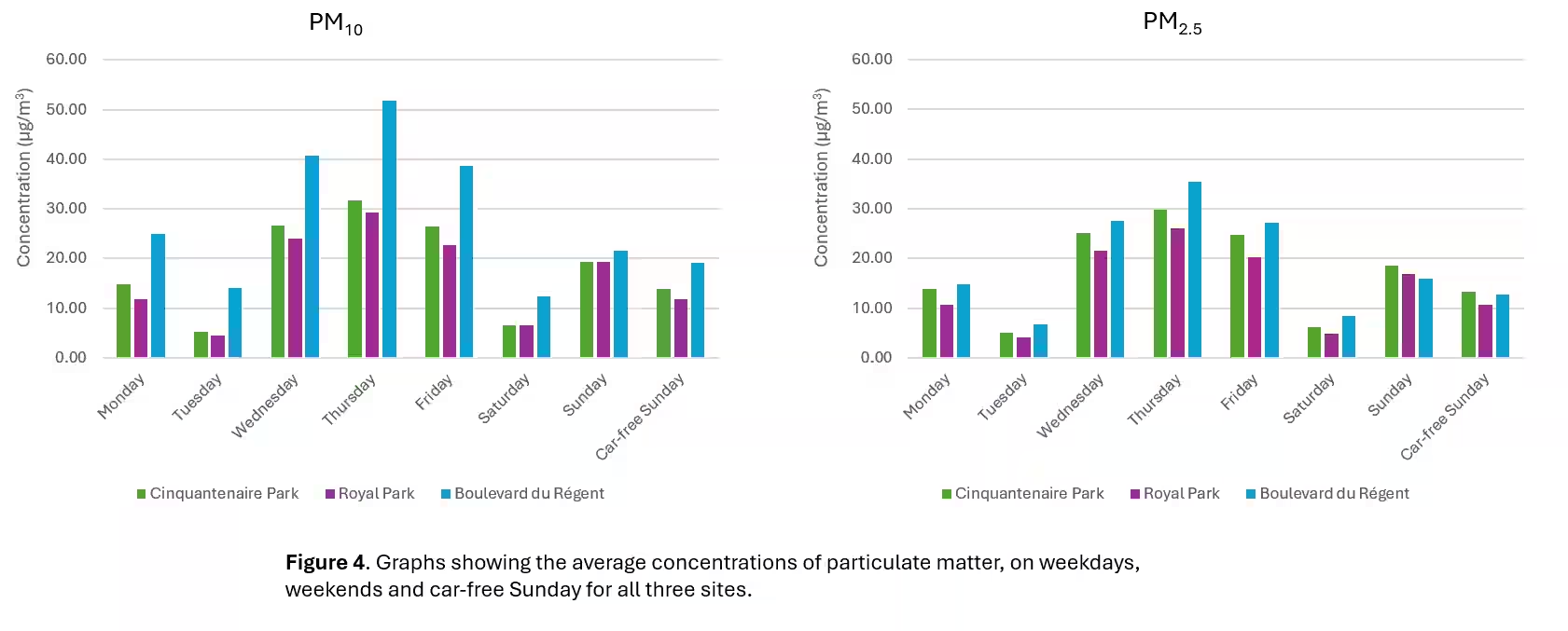

Particulate matter told a similar story. PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀ levels were consistently higher along Boulevard du Régent than inside the parks, indicating strong roadside sources.

The Day Without Cars produced a visible shift. PM concentrations fell by around 33% inside the parks and by 20% along the boulevard. NO₂ levels dropped even more sharply—by 54% on the boulevard and up to 48% in the parks—demonstrating the immediate impact of reduced traffic.

Weekday data showed clear morning peaks in fine particles along the road, while concentrations inside the parks were more stable. However, an unexpected effect emerged on car-free Sunday: fine particulate matter increased inside the parks during the day, likely due to dust resuspension caused by higher visitor activity.

Traffic context and exposure

Across all sites, NO₂ still peaked during the morning rush hour, suggesting that parks do not fully shield visitors from traffic emissions. On car-free day itself, NO₂ levels inside the parks were sometimes higher than on the boulevard, pointing to pollutants becoming trapped within enclosed green spaces rather than dispersing.

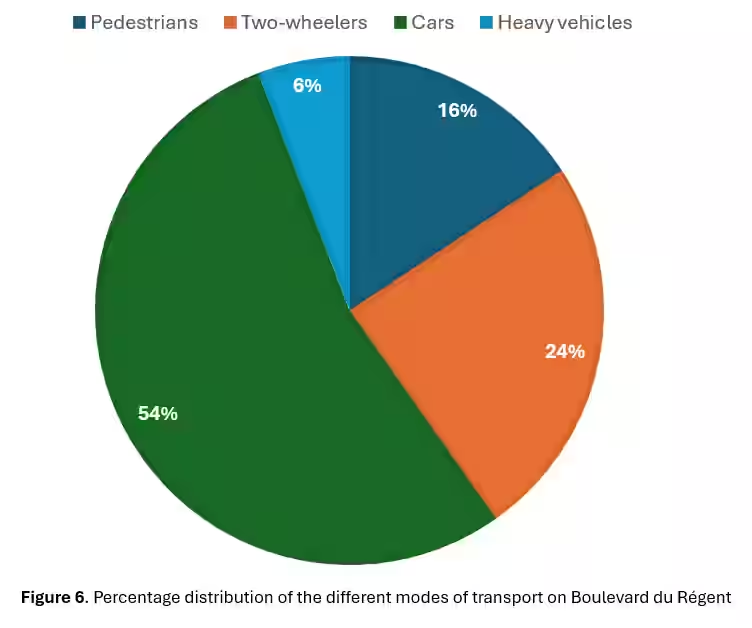

Traffic counts from a Telraam sensor on Boulevard du Régent indicate that roughly 6,500 vehicles pass through this corridor each day. The hourly distribution of traffic highlights pronounced peaks during commuting hours.

This context helps explain why pollution penetrates nearby parks. Pollutants generated during peak traffic periods can enter green spaces and persist, especially when dispersion is limited by surrounding buildings or vegetation.

How much can parks really reduce pollution?

To assess the real mitigation effect of parks, concentrations measured during the working week were compared with those on car-free Sunday. If parks effectively neutralised traffic pollution, differences between these periods would be minimal.

Instead, particulate matter levels were up to 35% higher during the week than on the Day Without Cars, with nitrogen dioxide showing a similar increase of around 33%. Peaks during rush hours appeared inside both parks, indicating that traffic pollution continues to influence these spaces.

Even on the Day Without Cars, pollutants were not eliminated. Once they enter a park, they can become trapped, sometimes resulting in higher concentrations than on adjacent boulevards where wind can dilute emissions more effectively.

Parks remain essential urban spaces, used by people seeking fresh air, exercise, and respite. Yet the data suggests that they are not consistently cleaner than surrounding streets. For runners, families, and older visitors, exposure can still reach levels above recommended thresholds. The Day Without Cars demonstrates what is possible, but it also underlines that lasting reductions in urban air pollution require sustained changes to traffic patterns, not temporary interventions alone.